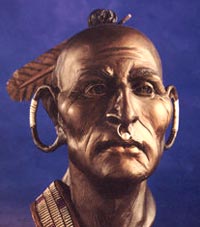

I. The Delaware Prophet Neolin

A. A. Origin of the term “prophet”—not a word that natives used to designate the religious leaders, but a term used by whites to compare these natives—unfavorably—to Old Testament prophets.

B. B. Changing Native Cosmology—the stress that native societies were undergoing during this time—due to the introduction of European microbes, for which natives had no cure, their increased reliance upon European trade goods, which they were finding they could no longer do without, the introduction of alcohol, with its debilitating effects on native societies—all worked to make native Americans more receptive to the new message that these native prophets were preaching. The dislocation of native culture that occurred because of the difficult adjustments natives had to make because of European contact prompted many natives to begin to question their long accepted cosmology, and the be receptive to new interpretations about their place in the world.

1. 1. Life after death—native beliefs held, before European contact, that all natives (except those who died in infancy) would go on to reside in an afterlife when they died—one’s place in that afterlife was not determined by how on lived one’s life while on earth. In part, this was probably due to the widespread native belief that one could travel back and forth between the present life and the afterlife through dreams. Native prophets adapt the idea of heaven and hell to attempt to compel native peoples to give up the European creature comforts and return to “traditional ways” to appease the Great Spirit. Those who chose to follow the narrow, difficult path would find there way to the Great Spirit in death, while those natives who remained unreformed would find themselves suffering the fire of a place similar to the Christian hell for all eternity.

2. 2. Proscribed behaviors—before European contact, native peoples had no proscribed behaviors; in other words, there was nothing equivalent to the Judeo-Christian Ten Commandment (although there were community pressures brought on individuals who did not act in what were perceived as the best interests of the community). This changes as prophets become more prominent—in order to meet the Great Spirit at the end of one’s life, one had to be monogamous, treat the one wife gently and respectfully, give up alcohol and other European trade goods, return to hunting the animals of the forest in a respectful manner (rather than killing most for their fur, to gain European trade goods). Native peoples were also called upon to give up the use of magic and spells (“witchcraft”), since that called upon assistance from the “Evil One” who closely resembled the Devil of Christianity.

3. 3. The Importance of a Transcendent Vision—the revelations were claimed by the various prophets to be the result of a vision in which the Great Spirit spoke directly to the prophet, and revealed the importance of implementing these new practices—and the renewal of traditional practices—to them. This, of course, made the visions more real for the natives—but raised doubts about their veracity among whites (who called these prophets “imposters” and “charlatans” as well) since these visions did not include visits from the Christian Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

C. C.T he Delaware—in order to better understand the emergence and importance of the Delaware Prophet Neolin, we need to have a greater historical understanding of the Delaware—or Lenape—people.

1. 1. Early European contact—the Lenape people inhabited the Delaware Valley of eastern Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and in southern New York when European traders entered the valley in the middle 1620s. By the 1640s, the Lenape had emptied the forest in their area of large game for the fur trade, the Dutch turned to peoples in the interior part of the country—particularly the Iroquois—to provide the valuable furs, and the Lenape were dependent upon selling handcrafts and other goods for rum with the Europeans.

2. 2. One-sided treaties—although the Lenape faired well when dealing with the founder of the colony, William Penn, his offspring were not as trustworthy. Most famously, the Walking Purchase (or Walking Treaty) was an instance of outright fraud. The “treaty” upon which the transaction was based was a forgery, and the purchase itself—which we discussed last class period—was gained under false pretenses.

3. 3. Withdrawal to the interior—shortly after the Walking Treaty experience, the Lenape abandoned their traditional homeland to reside in the interior of the country, away from contact with the Europeans. Depopulation and demoralization had taken their toll, and their population had diminished from estimated 11,000 to less than 3,000 by the 1730s.

4. 4. Creating a new ethnic identity—at first contact, they Delaware had no ethnic identity; they were merely scattered villages that shared two dialects of a common language. The crises they went through forged an ethnic identity for them, however, and by the 1730s they were no longer the thumb of the Iroquois, and were communicating with other native peoples (including the Shawnee) with ideas about a common native identity.

D D. The French and Indian War—as it is known in North American, but as Winston Churchill observed, it can perhaps truly be called the first World War, and Great Britain and France fought each other (with and through their allies) all around the globe—Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, North America, as well as each other in Europe. The war began an a young, inexperienced Virginia militia officer by the name of George Washington ambushed a French patrol, but were captured by French forces from nearby Fort Duquesne before they could escape.

1 1. The French Surrender in North America—Early French success in the conflict in North America cause the fall of the British government, and William Pitt became Prime Minister. Pitt committed large numbers of troops to the conflict in North America, which the French were unwilling to do (they were concerned about the Prussian threat on their eastern border in Europe, and therefore could not afford to commit the resources to North American that the British could. The result was the capture of Montreal by the British in 1760, and the surrender of French claims on the continent as a result. This agreement bewildered the native allies of the French, who did not understand how they could lose no battles, make no treaty, and still lose land in the agreement.

2. 2. Proclamation line of 1763—In order to bring government costs in North America under control, the British government made a series of agreements with native peoples in 1763, promising no further European incursion west of the Allegheny Mountains.

No comments:

Post a Comment